Everyone is processing current events in their own way. For my part, I decided to re-watch The Social Network. I once heard someone say that you haven't really seen a movie until you've seen it three times [1]. Wednesday night’s viewing was approximately my tenth. Hopefully, although I doubt it, I've learned a thing or two.

First impressions are important; ours of Mark Zuckerberg, in conversation with his soon to be ex-girlfriend Erica, sets the tone: he is ambitious, he is dismissive, he is arrogant.

As Mark shuffles home, the spectacular soundtrack from Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross commences with a tasteful, melancholy piano motif atop a brooding drone. What we hear hints to us exactly what we begin to see: a screaming tension.

Consider this juxtaposition, introducing the central dialectic—an intoxicated and newly single Mark pathetically blogs alone, disparaging Erica; meanwhile, in the same town as him, a literal busload of girls is transported to party with the next Fed chairman. Mark creates a website to compare the hotness of Harvard's undergraduate women; some of those women are, at the same time, playing strip poker at a final club he cannot get into.

"How do you distinguish yourself in a population of people who all got 1600 on their SATs?"

Director David Fincher masterfully uses intercuts throughout the film but first here to illustrate the iron law of social life in college: either you are in or you are out. Mark is out.

Nevertheless, he has a trick up his sleeve. He is one of the few to understand, however incidentally, that a new age dawns. The website link goes viral around Cambridge over the course of the night. The digital era promises irresistible and endless entertainment. Never mind the drunk and hot girls they have access to in real life, those boys' parties are now set on his terms.

Something inside Mark shifts in the wake of this experience. He seems to eagerly enter the Porcellian, one of the lauded final clubs, with Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss but cools as they explain their idea to him for a social website, HarvardConnection. Mark sarcastically rebuts the notion that they would help him rehabilitate his image. They explicitly state that the product differentiation is exclusivity, blissfully unaware that the man they're pitching isn't necessarily party to "girls wanna get with guys who go to Harvard".

"We row crew."

"Yeah, I’ve got a minute."

Mark's ambition lets him see something greater from that moment forward. His dismissiveness then allows him to decoy the Winklevoss twins while he programs a similar concept, and his arrogance leads him to conclude that he will do what the twins are not intellectually or creatively capable of doing, despite the plausible impression that he took their idea and ran with it.

The Social Network is a testament to Facebook's rise even as Mark seeks, above all else, to overcome the sting of rejection. He makes repeated barbs to Eduardo, who is being recruited by another final club, the Phoenix. He gets laid by a groupie in a bathroom stall but immediately thereafter feels the need to talk to Erica.

It's no wonder, then, that Mark is drawn to entrepreneur Sean Parker over his co-founder, Eduardo Saverin. Business disputes aside, Sean is cool—the boy wonder who made his name sticking up two middle fingers to the music industry. During their first meeting, he knows each of the restaurant staff by name, effortlessly orders fancy food and drink, and regales Mark with the story of how he crashed out of Napster. Sean is a partial reflection of Mark's self-actualization.

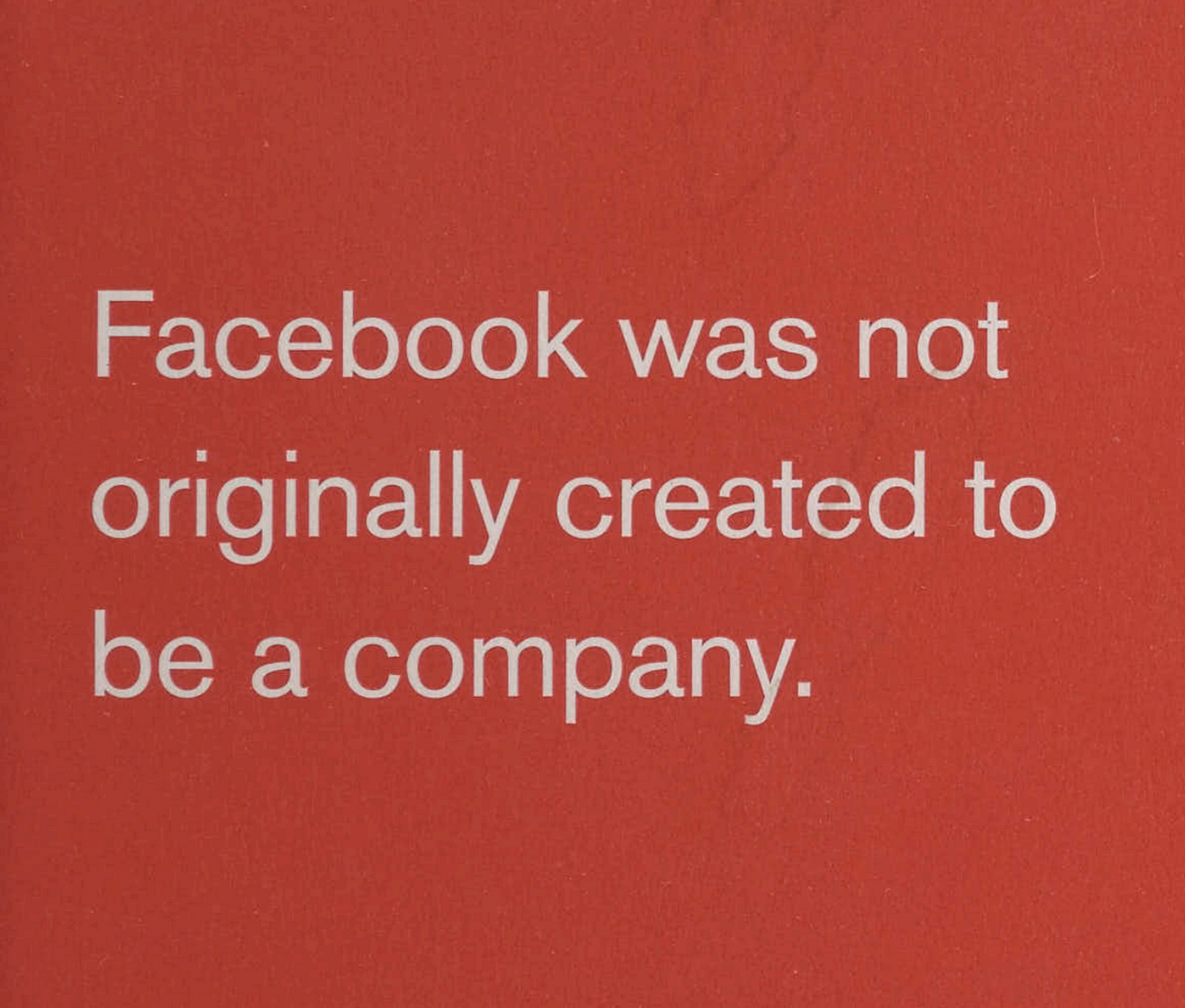

On the contrary to Sean, pro-advertisement Eduardo was sensibly thinking in the financial interest of the company but forgot one crucial point. As it was understood (then, at least), if the social factor is disrupted, so goes the entire potential business model of Facebook. Ads will always be an option, but zeitgeist is lightning in a bottle. Don’t let it out [2].

"A million dollars isn’t cool. You know what’s cool? A billion dollars."

Despite Mark’s newfound popularity being distant, at best, from his true self, he is protective of it. When Eduardo freezes the bank account that the business draws from for operating costs, Mark enlivens for the first and only time in the entire movie:

I am not going back to the Caribbean Night at AEPi! Did you like being nobody? Did you like being a joke? Do you wanna go back to that? ... I am not going back to that life!

Notably, Mark does not partake in any of the various celebrations happening around him and, by all accounts, piggybacking off of his labor. He watches from the rear of the throng as prospective interns take shots while trying to hack a web server. He is the cameraman as Dustin zip-lines into the pool. He is zoned out in the nightclub, Victoria's Secret model nearby, only intensely focusing on Sean's parable. Finally, he doesn't even go to the millionth-member party, at which Sean is busted for drug possession and drinking with under-21 interns.

"We lived on farms, and then we lived in cities, and now we’re gonna live on the internet!"

One gets the sense that Mark is at all times hovering above everyone else. Again, we see him outgrow an idol of his, this time Sean, as the latter's party boy behavior leads to arrest and bad publicity for the company.

The limitations of each of their perspectives are woefully apparent: Tyler and Cameron overly value esteem and gentlemanly behavior, Eduardo can't see why moving to California is a good idea and why ads are a bad one, and Sean is tossed about in a strange personality mix of wanton zealotry and paranoia.

For its success, Facebook must be greater than all of these characters, and Mark, well, Mark lives and breathes Facebook. They are in the moment; he is of the moment. He has the perfect blend of ambition, dismissiveness, and arrogance to see through all of it. The dialectic is synthesized; a new prototype of elite is born.

The movie concludes by arriving at one distinction between Mark, the company, and Mark, the person. There is someone he never quite outgrows: Erica. The girl who spurned him. Mark sends her a friend request on the very website he conceived and built (with a little help from his "friends") into a multi-billion dollar company, securing his fortune and his Godfather-like climb to the top. He refreshes the page over and over again but no notification appears. The digital era promises irresistible and endless entertainment.

"Do you ever think about the girl?"

"What girl?"

"The girl from high school..."

"No."

It's worth remarking upon a few caveats — the screenplay is famously off-center and unfaithful to the real life events of that time period. Aaron Sorkin's distinctively punchy dialogue combines with Jesse Eisenberg’s slick performance to offer an edge that Mark Zuckerberg’s actual persona has never for one second indicates exists, meaning that what we experience on the screen is 85% exaggeration and 15% perjury.

As I previously mentioned, the soundtrack is fantastic and contributes to this edge. In a general sense, many of the songs, aptly electronic, provide a sense that something (we do not know what exactly) is bubbling up.

The interpersonal relationships of college-aged students, some of whom are completely fictional, are likely irrelevant; something out of their control grasped onto them. The reality is that this movie principally originates from an interesting moment in recent history, the birth of social media, and therefore had little choice except to attach to these specific people and craft from them the most interesting version of the real story it could muster.

So, does The Social Network have any bearing on present-day matters? You be the judge.

I believe that a scientist looking at nonscientific problems is just as dumb as the next guy – and when he talks about a nonscientific matter, he sounds as naive as anyone untrained in the matter. Richard Feynman

Since I wrote this, you'll have to forgive me for believing there is one angle through which the light pierces, no matter how contrived.

A loose collective of individuals who cut their teeth in the dot-com era and in the immediate aftermath have extraordinary social leverage and increasing political leverage over the average American. More acutely, they’ve aligned themselves with the new presidential administration with varying degrees of vocality but each unambiguously. Although there are many more than four in this crowd, the central actors who’ve taken prominence are: Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Marc Andreessen, and Peter Thiel.

The motivations of the so-called "tech right" are, at the surface, more rational than some observers give them credit for. They express iron-clad ideological commitments in favor of technological innovation. In order to fulfill their idealistic vision within their demesne, they must behave pragmatically vis-à-vis one of the few actors with the capability to impede them: the federal government.

The American political left has grown hostile to them over the past decade while the president's transactional nature offers a seductive alternative. The left champions institutions both governmental and non-governmental; the emergent strain of thought [3] on the Internet, from its embryonic stage, has often been tinged with libertarianism [4].

Moreover, as Andreessen notes in his podcast interview with Ross Douthat, leaders in the technology space had an agreement of sorts with Democrats in the past. One can easily argue, therefore, that none of this logic is new—the political-economic landscape really has shifted. It’s just business. That these men’s political opinions may have trended right over time or, in the case of Thiel, have been that way is immaterial, right? To each his own?

If only it were so simple. It’s evident that realpolitik is intuitive to these executives, but I take note how they’ve knowingly hitched their ride to a precarious wagon. They’ve done so with gusto.

Musk, current éminence noire of the president, takes unprecedented steps to decimate the public interest technically housed within the executive branch. Opponents find difficulty raising an effective spiritual defense due to its sheer velocity but also because the conversation is fraught. The salience of both wokeness and the debt burden as political topics have finally reached saturation.

Thiel, former éminence noire, took to the Financial Times in January to outline what this moment represents:

The apokálypsis is the most peaceful means of resolving the old guard’s war on the internet, a war the internet won.

He proceeds to write esoterically and conspiratorially before arriving at that point again:

There will be no reactionary restoration of the pre-internet past.

Who said anything about that? I sense a theme. What's clear from the events of the last few years, months, and weeks is that we've arrived at the limitation of our perspective, the public [5]. Like the other character portrayals in the movie, we are left behind while Zuckerberg et al. gleefully take their next step.

The well of political discussion in America is poisoned for the left and right alike. With ever increasing political instability, we are experiencing a supposed re-imposition of “law and order” that is neither lawful nor orderly. Americans hear claims of a “massive mandate” [6] and political will justifying these rash and chaotic changes perpetrated by Musk and DOGE, but which coincidentally do not have the imprimatur of Congress or the courts.

Meanwhile, Zuckerberg now wears custom designed clothes with Greek and Roman inscriptions on them [7]. Musk tweets "vox populi, vox dei" to caption online polls on a website he owns and which, ironically, prioritizes his vox over anyone else's. It would seem Zuckerberg considers himself Caesar, and Musk considers himself Deus.

Credit should be given where credit is due: they perceived first the widening gyre. Meta and its ilk must be greater than us. As Horkheimer and Adorno might have seen in their worst nightmare [8], the tech right have been blessed with the vision of the cross, Metropolis style: In hoc signo vinces.

I find this to be a shame. I certainly didn’t envision it while I was being quasi-raised by the Internet. The beauty of the baud, the utopian Internet promulgated by open protocols and services such as Usenet and further intimated by the arrival of social media, this was not the Internet they elected to deliver. Rather, walled gardens, closed-source algorithms so gently guiding which creators and what content we consume, and planned obsolescence and opacity of hardware.

The tech right were the forerunners not in creating the Internet but in commercializing it. They wrangled the pastoral geography of cyberspace and constructed a panopticon. Now, anywhere the average user turns, everything is for sale: time, attention, privacy, to name a precious few.

How much money have venture capitalists and entrepreneurs extracted out of the life works of luminaries like Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson, Richard Stallman and Linus Torvalds? Every subroutine executed in C, every server running a Linux kernel, what of them now? None of the above names are included as patron saints in The Techno-Optimist Manifesto. Silly Jonas Salk, he couldn't patent the sun!

Let me be clear: I generally support free-market enterprise and risk-takers being rewarded for goods and/or services they provide to consumers. I oppose the haughtiness of billionaires who seek regulatory capture, who turned their backs first on the original principles of techno-optimism before throwing it into the faces of the public.

Per usual, John Ganz makes an incisive point in this vein in one of his recent essays:

Musk’s total idiocy is structural: it goes back to the very origin of the Greek term idiotes, a person who cannot understand the shared political life of the city. These people cannot understand that their wealth and power are not their sovereign creations but the shared product of the wider state and society that supports and sustains them.

What Zuckerberg, Musk, Andreessen, and Thiel, representative of many others, are conjuring here is not optimistic, nor is it meaningfully libertarian. Does it make sense to destroy benign state capacity in one section, independent agencies accountable to two branches of government, by metastasizing it in another section, a newly-crowned unitary executive? Who is he accountable to, exactly? [9]

It is self-preservation. From their viewpoint, the Internet of the 21st century is, kind of, their thing. It is the past and present carrier of their ambitions, the bringer of their wealth, and, most importantly, the basis of their legitimacy as elites. Any threat to it is existential to them and they've explicitly stated as much.

Democrats crossed a cultural and regulatory line in the later-Obama and Biden years; that much I understand and even sympathize with. I cannot condone, especially with such wrath already wrought, that all the other side needed to do, in exchange for allegiance, was present a dotted line.

We return thence to The Social Network. I could not escape frustration as I watched. No amount of movie magic by David Fincher, Aaron Sorkin, or whomever, could absolve the obvious infidelity. Sell your product—fine—but do not pretend. If it was ever out of beneficence, it is no longer. They are doing what they are doing because it will feed them influence. It will avoid regulation of social media and artificial intelligence by the government and avoid backlash from the public. It will make them greater. In a clever stroke, they fit among the new elites qua “counter-elites”.

Nor could I escape the realization that I, this entire time, had also been had by the guy who is not an asshole but is trying so hard to be. An entire decade, longer even, during which technology was cool in the mainstream slipped through my grasp as what actually made the Internet great, RFCs painstakingly building TCP/IP, an R&D miracle from a government-supported monopoly, etc., was in the process of getting choked out—a different type of software was eating the world.

One of these knuckleheads even has the audacity:

The way to greater American prosperity is encouraging people to move from lower productivity jobs in the public sector to higher productivity jobs in the private sector.

They are well aware, better than most, that the Internet is an outcrop of ARPANET, and the American flag was planted on the goddamn moon by the goddamn National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The tech right have legitimately impressive resumes; they have accomplished a lot; they are ambitious, successful computer people. At the same time, they have become dismissive and arrogant.

To the extent that they are genuinely-held beliefs, the technological spirit they inhabit is agreeable. Peter Thiel and I would disagree, however, just who represents the old guard. Twenty to twenty-five years ago, the contradiction resolved in their favor. A new cadre of elites were devised, as they always are, underneath the banner of idealism. Unfortunately, in the case of these men, the banner they profess is now besmirched.

But who's to say a new question isn't moving its slow thighs somewhere in the sands of the desert, its hour come round at last? The tech right might still see themselves as the disrupters [10], but I somehow don't imagine they intend to suffer fools gladly, such as the next generation of 20-year-olds wearing hoodies and fuck-you flip flops with business cards to match, reading, "I'm the CEO, bitch."

[1] I could swear that it was Roger Ebert but can’t find any satisfying search result.

[2] Even today, about half of humanity uses Facebook in a given month. On the other hand, countless startup social media sites before and after Facebook's time are wasted away.

[3] The adjective “emergent” rather than, for example, “subtextual” was one of the tougher word choices of this post. As all of us have experienced, the thunder of expression on many Internet services and platforms, even if prone to whiplash, favored the left for a long time. Now it is less clear. I think “emergent” is right, nonetheless. To use an example I am intimately familiar with, reddit exploded for Bernie in 2015 but before that highly supported Ron Paul. Libertarianism is not just the substrate of the medium, it is also the id.

[4] The 90s Cypherpunks, who trace a lineage to crypto, are a notable example.

[5] The contingent of citizens who support are equally as included within this sentiment as those who object.

[6] The margin of difference of the popular vote in the 2024 presidential election was less than in 2016.

[7] I hadn’t seen the Aut Zuck shirt until reading Natalie Ponte’s essay on a similar theme as this one. It deserves a shout-out and is worth the read.

[8] Or, perhaps, their most divine dream.

[9] One of the corollaries to the Supreme Court decision granting nearly total criminal immunity is that the singular check on the executive branch is 67 senators voting to remove. In this era of hyper-partisan politics, at least ~17 senators must vote against the leader of the party.

[10] They sure are disrupting something.